Welcome back.

As promised, our next story is remarkably short—only eighty-six words. It’s so short, in fact, that I can provide it, in its entirety, in this post.

‘Alas,’ said the mouse, ‘the whole world is growing smaller every day. At the beginning it was so big that I was afraid, I kept running and running, and I was glad when I saw walls far away to the right and left, but these long walls have narrowed so quickly that I am in the last chamber already, and there in the corner stands the trap that I must run into.’

‘You only need to change your direction,’ said the cat, and ate it up.

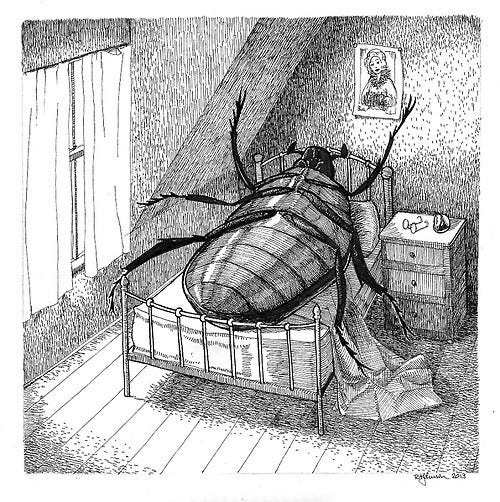

This is “A Little Fable” (“Kleine Fabel,” in the original German) by Franz Kafka. Kafka is likely renowned even outside literary circles: the image of Gregor Samsa from The Metamorphosis, transformed into a cockroach in his bed, has evolved into a useful metaphor for the dehumanizing realities of late-capitalist life—a slow erosion of spirit and body by the mechanisms of post-industrial labor culminating in a violent realization of one’s own extrication from recognizable humanity.

“A Little Fable” does not provide the same amount of raw literary material present in The Metamorphosis. But I’d like to offer that its brief content is more generative than may appear at first glance. Each of its eighty-six words can be connected to a larger connotative system of meaning through which any given reader can glean its nightmarish network of signification. We do not need a mammoth text to locate mammoth meaning.

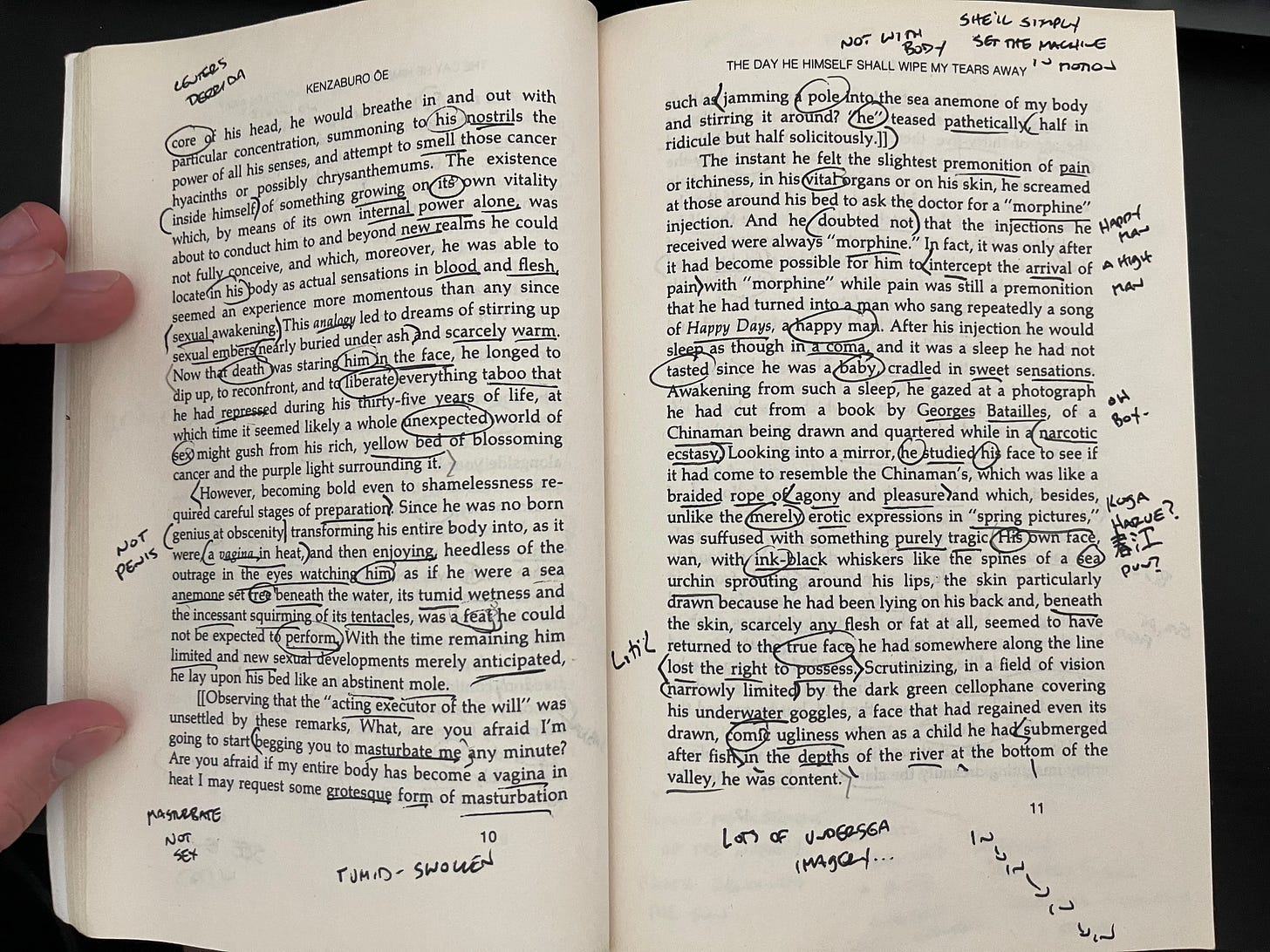

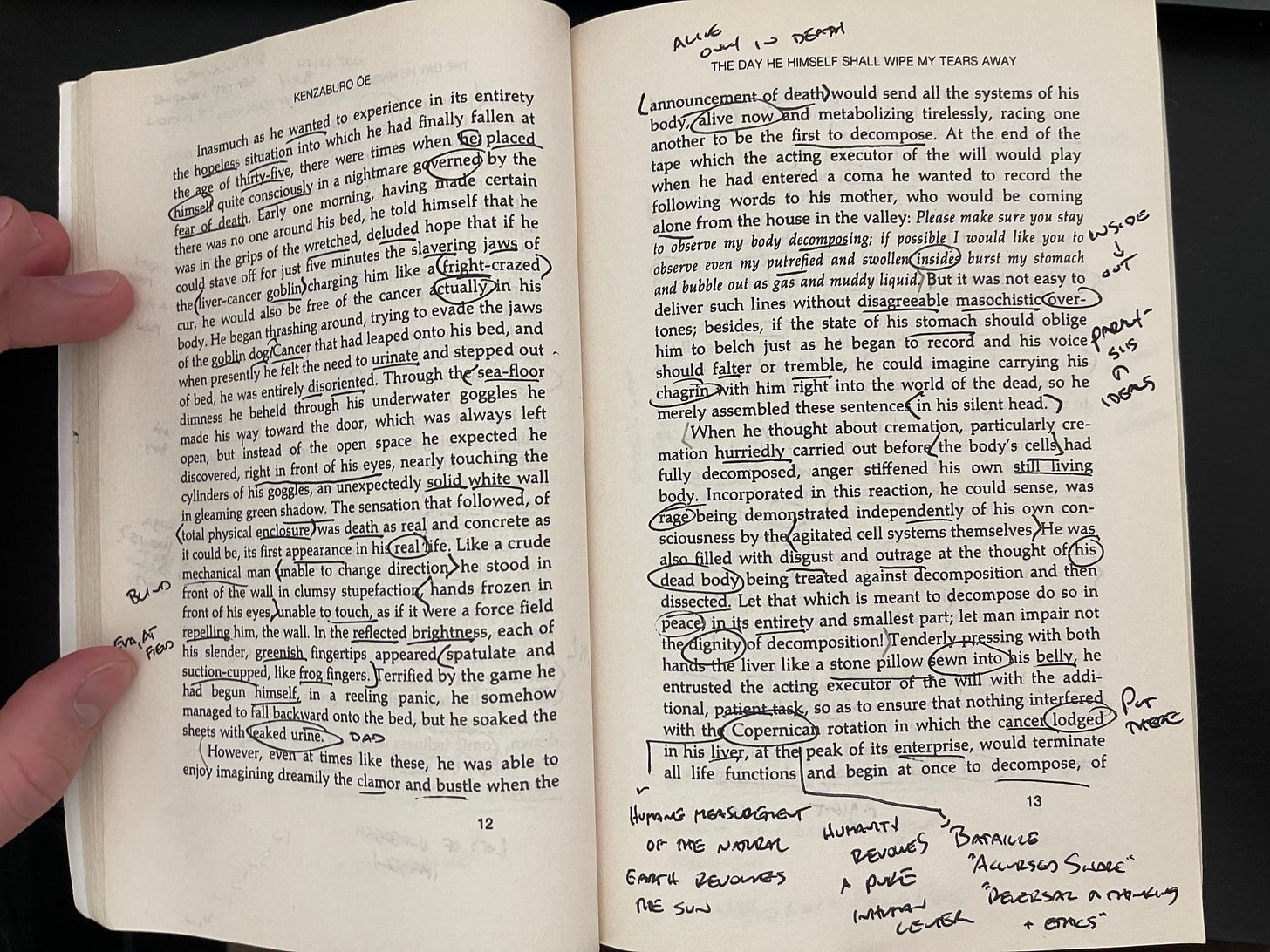

To give an idea of the scale of signification that can be present in a small amount of text, I’ve included two photos below—some of my notations on the Ōe Kenzaburō novella The Day He Himself Shall Wipe My Tears Away. While messy, I think they can provide, at least visually, a model for the sheer amount of preliminary exegetic work that can be pulled from a relatively small amount of text.

As an experiment in our future posts concerning “A Little Fable,” I’d like to approach the story structurally. How can we attach each element of the story to a larger connotative network of associations? What can we learn about the story through these associations? And, most importantly, how do we understand ourselves (as readers and humans and mice and cats) as an inextricable presence within our systems of association?

Busy as ever. Back soon with more on “A Little Fable.”

All my love,

rmc

P. S., a quick reminder that, starting with this series on Kafka, each final post (“Another Thought”) will only be available behind a paywall with the additional luxury of recordings of the post.